In part 1 of my T-shirt series, I fitted and adjusted the pattern for the T-shirt. In this installment, I see how well it fits by making a “muslin”, in this case a T-shirt out of fabric I won’t cry much over if it doesn’t work out.

I have this cut of heather gray jersey knit with hot pink stripes.

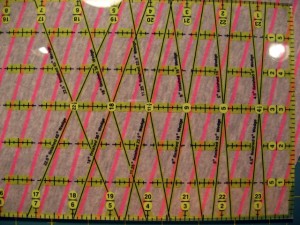

It’s not high-quality knit; it’s really thin. But the big problem with this knit is that it is off grain. The stripes are printed at an angle relative to the knit lines in the fabric. In fact, I think the knit lines may not even line up properly with the selvages. This closeup photo should show you what I mean.

My Reader’s Digest Guide to Sewing says I should just toss fabric like this, as the grain can’t be corrected and the shirt will fit incorrectly if not cut along the grain lines. Instead, I will position the pattern pieces on grain and cut with the stripes at an angle, producing a garment with slanted stripes. Laying out and cutting this fabric feels like a trip to the Mystery Spot.

I rooted through my collection of jersey knits to find a suitable fabric for the collar. My three choices were white rib knit, and yellow or turquoise jersey. After stitching a few test samples on the serger, I ultimately went with the turquoise.

I decided to use a three-thread overlock stitch on the serger to do all the seaming and collar attachment. A three-thread stitch is stretchier and has less bulk, but is less strong than the serger’s 4-thread stitch.

I discovered the “flat” method of T-shirt construction from the book Successful Serging by Beth Baumgartel, and it’s much better than the pattern instructions:

- First, join one of the shoulder seams; this gives you a continuous neckline.

- Serge the collar on while the neckline is still flat.

- Close the collar by serging the other shoulder seam.

- Hem each sleeve, then serge them both to the body.

- Serge one of the sleeve + side seams – this gives you a continuous waistline.

- Hem the waistline while flat.

- Then serge the remaining side seam closed.

The big nightmare for me in the past has been that I always had difficulty stitching clear elastic into the shoulder seams, whether by conventional machine or serger. (The clear elastic serves to reinforce and stabilize the shoulder seam, to keep it from stretching out of shape when worn).

This time I took a hint from the book The Best Of Sewing With Nancy. In the chapter on lingerie construction, she says to not cut the elastic to size. Instead, just keep the elastic on the roll and run a few inches past the end where it joins the fabric, to make the attachment process easier.

So I ran the clear elastic into the serger first, then layered the shoulder seam an inch or two later. On the first shoulder seam, this worked very well.

So then I serged on the collar, while the neckline was still flat. This beats quarter-marking and stitching “in the round” any day of the week.

On the second shoulder seam, since the collar had already been attached, I couldn’tstart the elastic before the shoulder seam because I would get elastic in the collar. I had to serge over the collar, then feed the elastic right at the point the needle started on the shoulder proper. I ended up missing the first inch or two of the shoulder seam when closing the collar.

Then I closed the shoulder seam by threading the serged threads back into the seam using a tapestry needle. (This process is illustrated near the end).

Next, I hemmed the sleeves. I would have used the new coverstitch machine to do this, but my coverstitch machine is malfunctioning (topic for another post) and it ate the sleeve fabric.

I had enough fabric left to cut two new sleeves, and I simply hemmed them with a zigzag stitch on the conventional sewing machine. My prior attempts at hemming with other approaches, including twin needles, have not been successful.

I set up double-barreled sewing machines for the remainder of the construction.

I did use some Dritz Washaway Wonder Tape to fix down the hems and stabilize them before zigzagging. Many thanks to the Male Pattern Boldness blog for introducing me to this stuff.

Applying the Wonder Tape to edge of hem.

I serged on both sleeves and serged down one entire side of the shirt. Then I opened up the shirt, and pressed and taped down the waist hem.

I stitched the hem on the conventional sewing machine, then closed off the remaining side seam with the serger.

After closing the serger tails on the side seams, the shirt is complete. Here’s the best method I’ve discovered so far for closing the serger tails. I still need practice.

I use a standard needle threader to pull the serger tail through the eye of a tapestry needle.

Next, tie an anchor knot at the end of the tail. I am experimenting with tying the knot around a stiletto to try to get the knot as close to the seam as possible.

Next time, we’ll have a photo of the completed project.

The flat method of serging a tee shirt is not my choice. Yes it is easier, but in the end, having to close those seams afterward leaves everything looking sloppy, not matter how much time you take to bury the free ends ( fussy and added time for unnecessary handwork). I noticed you took the extra step of flat felling your button shirt seams, why wouldn’t you take the same higher end construction on your tees?

Your method of hemming is also very home-madish. The best way to finish a knit hem is to coverstitch. If you have a coverstitch machine great, but many sewers won’t invest the money. I have an industrial coverstitch machine but sometimes it can be a PITA, so to preserve those last few hairs on my head, I sometimes use the old serge and twin-needle technique that you mentioned did not work for you. You might give it another try, perhaps using another machine. I find the resulting hem looks nearly identical to a factory finish, does not stretch out of shape, doesn’t require any taping, and still has the ability to expand and recover.

Hi John,

Perhaps I need more practice – but finishing collar, cuffs and hems “in the round” has often led to some bizarre puckering and re-dos with the serger.

At the time I made this T-shirt, I had purchased a coverstitch machine but had to send it back because it was damaged in shipment. I have one now (the Brother 2340CV). I just purchased some more jersey fabric this weekend, and springtime T-shirts are on the project calendar in the not-too-distant future. The Brother coverstitch is also a PITA to operate, but I agree it gives a much nicer result on the hems than my home-made technique.